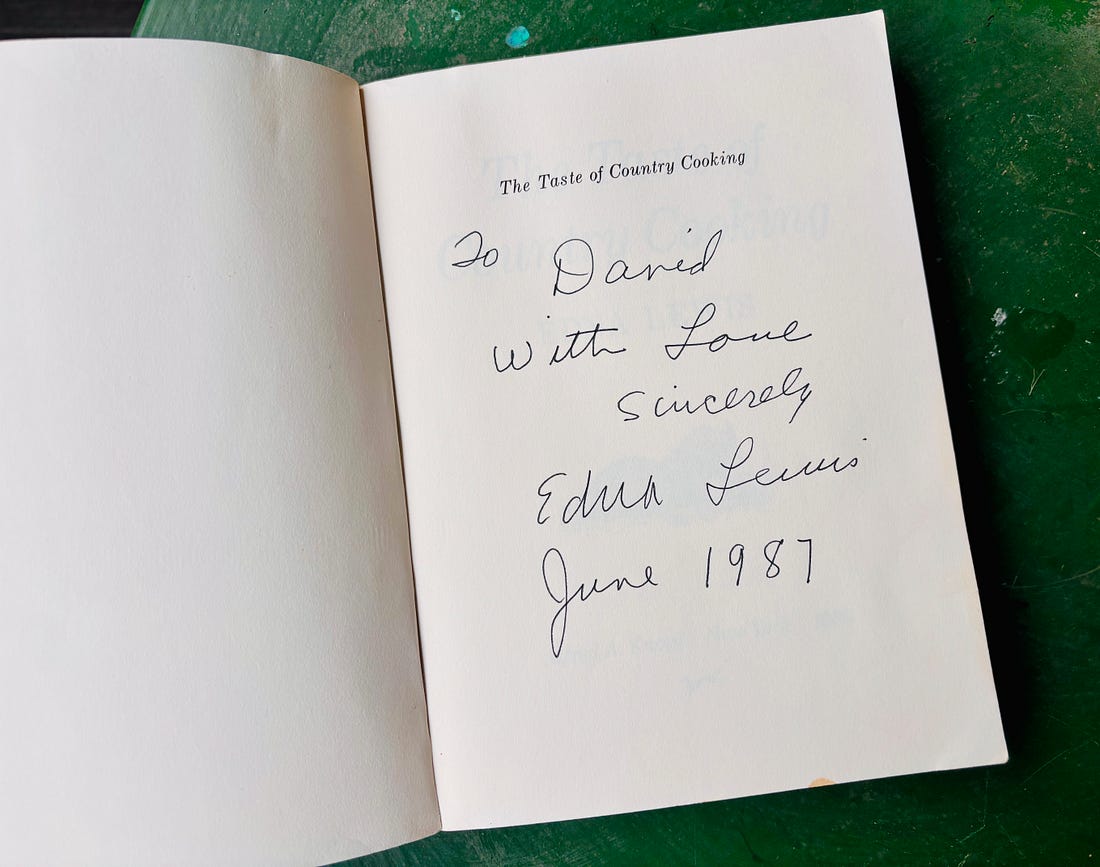

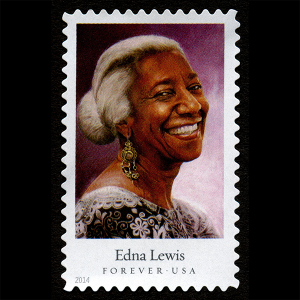

I feel like so much is going on in the world that it’s just too much to take everything in. Sometimes I wake up in the morning and feel like I’m in a whole new world, as I did today. In the arc of my life, I went from washing dishes, to working as a line cook, then to rolling dough and peeling apples in restaurants, to where I am now. I never felt like I had imposter syndrome because I feel like I’m just continuing to do what I’ve always done: peel apples, bake cookies and cakes, and yes, I still wash dishes. While there’s no word for “home baker” in French, that’s who I am now. Being at home has its advantages, but I do miss working in restaurants with other people, some from vastly different cultures, and others with backgrounds similar to mine. I’ve worked alongside people who’ve shared with me how, in their country, everything got taken away from her family — their house, their money and savings, and their business — and they came to the United States to make a new life for themselves. Another fellow had crossed the Pacific Ocean on an overcrowded boat, a voyage that took several months, and many people didn’t make it. It’s incredible what humans can do and overcome. It was so different than my life and I couldn’t imagine doing what they did. But they did it. Recently I opened up my copy of The Taste of Country Cooking by Edna Lewis. The granddaughter of a freed slave, she and her seven siblings grew up in Freetown, a Virginia community founded by other freed slaves that was composed of eleven families. The book reflects on a different time and a seemingly gentler place, and she bucolically recounts her childhood, skimming cream from crocks of milk to churn into butter, making jelly from wild grapes, and wine from dandelion blossoms, as well as beer, from persimmons. There was also the weeding of corn fields, gathering hickory nuts to make cookies, pickling wild mushrooms, hand-churning ice cream, and enjoying her mother’s homemade liver pudding, made after the hogs were butchered. I’m not sure how many kids today would enjoy liver pudding, or doing chores, but her writing is so evocative that I could imagine them. Miss Lewis, as she was later called, grew up and eventually moved to New York City where she was hired as a chef, a rarity for a Black woman in those days. She began as the chef at Cafe Nicholson in 1948, then later in life, in 1988, became the chef at Gage & Tollner when she was 72 years old. In between, she did everything from pheasant farming and catering to teaching cooking classes. She was prodded by editor Judith Jones, who edited Julia Child, Madhur Jaffrey, James Beard, and Jacques Pépin, to write her now-classic book, The Taste of Country Cooking. It’s so beloved that there was a 30th anniversary edition of the book, and coming soon is a 50th anniversary edition. (For a more complete picture of Edna Lewis, there are some in-depth biographies of her here, here, and here.) By the time I met Edna Lewis, her hair had turned a ravishing grey color and she wore it tightly pulled back, which emphasized her striking features. She was one of the most beautiful people I’d ever seen, and I was fortunate enough to meet her and have her sign a copy of her book to me. After she passed, her likeness was featured on a U.S. postage stamp. I recently decided to clean out my freezers. Yes, freezers, plural, and I’m hoping to tackle my kitchen cabinets next. In one cabinet I have a little jug of sorghum molasses from who-knows-when. Maybe when I made Sorghum ice cream with sorghum peanut brittle? Every time I come across it, I think, “I need to use this.” It gets brought to the front of the cabinet, waiting for its turn, then eventually gets pushed towards the back again. But when I saw that Edna Lewis had a recipe for Warm Gingerbread with Sweetened Whipped Cream in the book that called for “1 1/2 cups sorghum molasses”* — finally, I’d found just the right place, and time, to use it. The molasses that many of us know is made from sugar cane or sugar beets. Sorghum is a grass that arrived in America from Africa. It became widely grown and used in the American South, although sorghum syrup (as it’s also called) is not as widely known, or as available, as cane sugar molasses, which is a shame because it’s really tasty stuff. Sorghum molasses has a tangier, more complex flavor than standard baking molasses, which is called light or mild molasses. It falls between those and blackstrap molasses; the latter is very intense and too assertive for most baked goods. When I was revising Ready for Dessert, I noticed the most prominent molasses brands in the U.S. have changed how they labeled molasses, which gave me a bit of anxiety, trying to explain them to my dear readers, so I asked a friend coming over from the States to bring them all to me so I could taste them myself. Because that’s who I am. Brer Rabbit, one of the major brands, sells three types of molasses: Blackstrap, Mild Flavor, and Full Flavor. The blackstrap was very strong and bitter. I didn’t taste a big difference between the Mild and Full Flavor molasses, but they recommend the Full Flavor for baking and the Mild as a sweetener. Grandma’s sells Original and Robust molasses. The latter isn’t called blackstrap but tastes like it. Molasses isn’t used much here in France, but mélasse is available in natural food stores and is very strong, similar to blackstrap molasses. So if I have to use it, I’ll cut it with honey. In the UK, there’s treacle, and here is how it compares to molasses. The first gingerbread that I made from the book turned out quite dense, as you can see above. It tasted great (Romain loved it…), but the texture wasn’t what I was expecting. So I made it again without the 1/4 cup of oil, which I used in place of the lard** that the recipe called for, and it came out beautifully. And we’ve been snacking on it all week. Edna Lewis’s final book, published in 1988, was titled In Pursuit of Flavor, which echoed something my grandmother, who was from the same generation as Miss Lewis, complained about. She couldn’t tell if it was because she was getting older, but to them, food had less flavor than it did when they were growing up. However, there’s no denying that this gingerbread is packed with flavor. And like Miss Lewis’s words, the warm spices and flavor of the rich, bittersweet molasses hark back to a different time, one of civility and grace — and getting a taste of both of those can’t be beat. Edna Lewis’s GingerbreadOne 8-inch (20cm) cake; ten to twelve servings Adapted from The Taste of Country Cooking by Edna Lewis Like many snack cakes, this one is made in a square cake pan. If you don’t have an 8-inch (20cm) square cake pan, according to this (calculated by someone better at math than me), you can use an 8-inch (20cm) round cake pan with a little math. I haven’t tried it but I’m fairly certain you could bake it in a 9-inch/23cm round cake pan if that’s all you have. It may come out thinner and you might have to adjust the baking time up or down. Just go by the toothpick test to test for doneness, which is invariably accurate. Do make sure to give the batter a good whisking if you see any little lumps in it. They won’t dissolve during baking, so you want to make sure there aren’t any before you pour the batter into the pan. 2 cups (280g) all-purpose flour 2 teaspoons baking powder, preferably aluminum-free 1/4 teaspoon baking soda 1 tablespoon ground (dried) ginger 1 teaspoon ground cinnamon 1/2 teaspoon ground cloves 1/2 teaspoon salt 1 cup (250ml) water 8 tablespoons (4 ounces/115g) unsalted butter, room temperature, cubed 2 large eggs, at room temperature 1 1/2 cups (480g) molasses (see notes in post) Butter an 8-inch (20cm) square cake pan. Dust the inside with flour and tap out the excess. Cut a piece of parchment paper into a square to line the bottom. Preheat the oven to 350ºF (175ºC). In a large bowl, whisk or sift together the flour, baking powder, baking soda, ginger, cinnamon, cloves, and salt. Heat the water until it’s very hot in a small saucepan. Remove from the heat and add the cubes of butter. Stir until the butter is melted, then stir the water and butter mixture into the dry ingredients. Mix in the eggs one at a time, stirring until smooth, then mix in the molasses. If the batter is lumpy, whisk the batter briskly until it’s completely smooth and lump-free. Scrape the batter into the prepared cake pan. Bake the cake until it feels set in the center and a toothpick inserted into the middle of it comes out clean, 35 to 45 minutes. Cool the cake in the pan on a wire rack. The cake can be served warm or at room temperature. To remove the cake from the pan, run a knife around the outside of the cake to separate it from the cake pan, then tilt the cake out of the pan. Peel off the parchment paper, then place the cake on a serving platter. Serving: Edna Lewis served this cake warm with whipped cream, which she made by whipping 1 cup (250ml) of heavy cream with 2 tablespoons of sugar and 2 teaspoons of vanilla extract. Modern tastes might reduce the amount of sugar in half.

*Although I see some websites refer to it as sorghum molasses, it’s often called sorghum syrup. **Lard isn’t commonly used in baking in France. It’s available in supermarkets, called saindoux, and is mostly used for greasing the griddles when making crêpes. You're currently a free subscriber to David Lebovitz Newsletter. For the full experience, upgrade your subscription. | |||||||||||||||||||||||

Tuesday, January 20, 2026

Edna Lewis's Gingerbread

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment