In the old days of blogging, to get noticed, you posted a recipe and call it “The best _______[Insert a dish here] ever!” Later, that evolved into “life-changing.” I’m sorry, but a cure for cancer or world hunger is life-changing. A way to cook rice isn’t quite there. Some food magazines did something similar, charting their course in print to reach “The best way to cook salmon!” I tried that tip of spreading mayonnaise on salmon before cooking it, and it just tasted like salmon with hot mayonnaise spread on top of it. And don’t get me started on replacing butter on a grilled cheese sandwich with mayo. Grilled cheese sandwiches should not get messed with: no kimchi, apples, sweet potatoes, or mushrooms, and hold the mayo. But I will allow it if you use it to stick extra cheese on the outside to make the exterior of the sandwich extra-crispy with crispy cheese. I haven’t tried it, but I suppose that could be close to life-changing…

In my career, I’ve avoided the term “The Best” since taste is subjective, and I don’t post or print recipes that I don’t think are “The Best.” Why would you share a recipe if it wasn’t the best you could come up with? It isn’t me who names “The Best” œuf mayo in the world every year. Because I’m not writing for search engines, there’s no reason to lie to you. It’s up to someone else to bestow that honor in France.

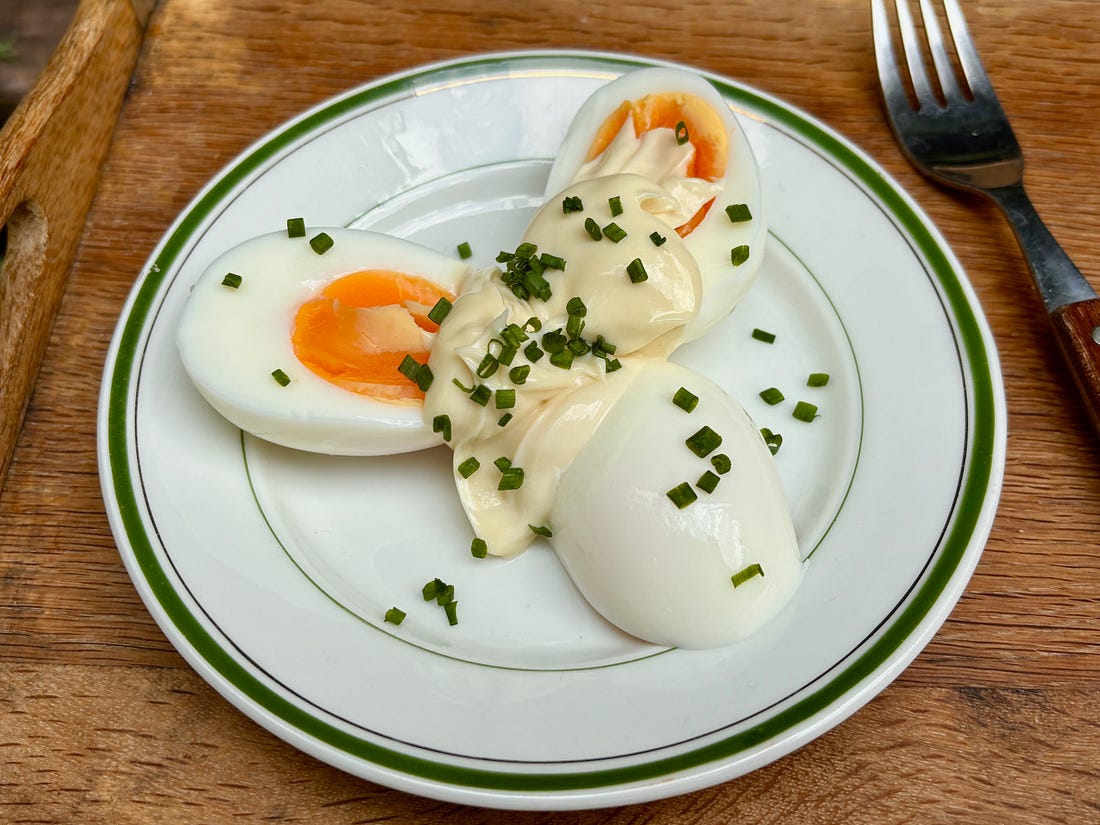

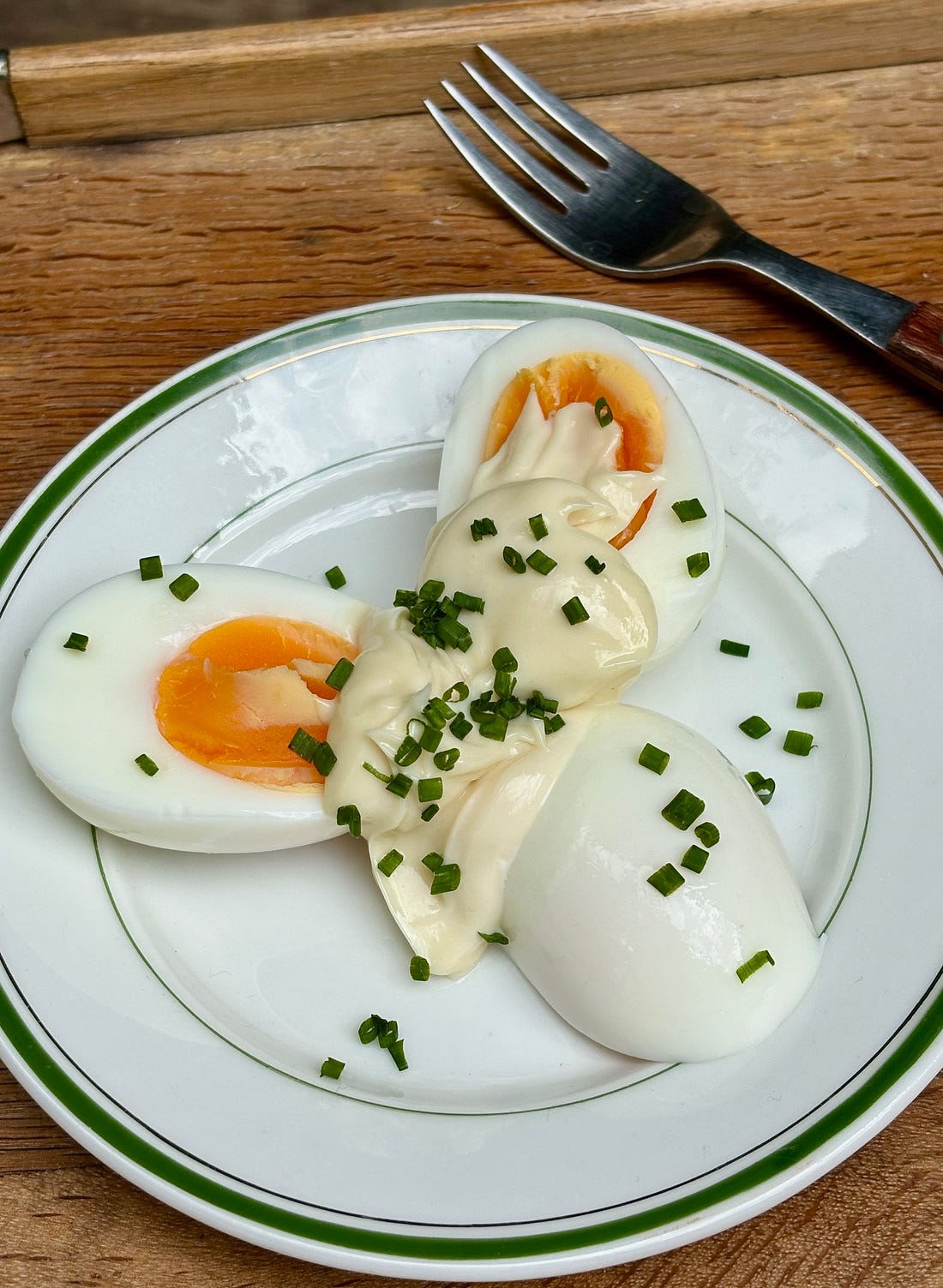

For those of you unfamiliar with œuf mayo, it’s a beloved café classic in France. It’s basically a hard-cooked egg served with mayonnaise. If that sounds odd to you, think of it as pre-deconstructed egg salad. The first time I heard of it, it sounded a little strange to me. But now, I order it every chance I get. When I was writing this post, I found an old quote from me in the New Yorker, where I said: “I think I’m the only American who likes that dish.” Thinking about it now, though, we do have our deviled eggs. (I also came across an article by Dorie Greenspan in the NYT about the œuf mayo, and a number of commenters—by people who don’t live in France—remarked that no one eats this dish anymore in France…which, as you can see by the copious amount of photos in this post, isn’t the case.) The dish was falling out of favor, so an organization was founded by a French food critic and a journalist friend in 1990 to save (sauvegarde) the dish; the Association de sauvegarde de l’œuf mayonnaise, otherwise known as the A.S.O.M. You can join for €39, and I probably should. But I’m still waiting for the esteemed Club des Croqueurs de Chocolat, a group of people who gather to taste different chocolates in Paris, to send me an invitation. I’ve heard they only have 150 places, and someone has to leave before a place opens up, so I’m sure that’s the reason. It’s been twenty-two years, though, so maybe they have another reason. On the other hand, there’s no shortage of chocolate at home for me to taste.

I’m also waiting my turn for the Ordre du Mérite agricole, an honor bestowed on people who promote French agricultural goods, as in, the foods of France, which several of my friends got who don’t live in France, so I’m pretty sure that’s coming. I just don’t know if I can wait twenty-two years, when I’ll be 88, to get it. 🎖️😊

While you can still find œuf mayo on lots of café menus — many of them homely, which is kind of the idea — younger chefs are getting on the Œ.M. bandwagon and coming up with their own unique and updated versions. The one farther up above, from Le Cornichon, gets right to the point, serving a whole egg with little pot of tartare sauce. It’s a nod to the hard-cooked eggs people snacked on in cafés. Even though it’s a little messy to crack at the table, it’s had not to like the minimalist presentation The one just above is a gussied-up version of œuf mayo at Soces, a restaurant that specializes in seafood, so Chef Marius de Ponfilly adds trout eggs, putting eggs on eggs. It’s a pretty good rebuke to everyone who thought French cuisine was finished. It’s been refreshed and brought back by a new generation who are having fun with it and not taking it so seriously.

The version at Grande Brasserie is pretty excellent, which took the œuf honors two years ago. The eggs are topped with a puddly spoonful of mayo, and the celery remoulade underneath it takes it up to 11. Pairing these two café classics is a balance of upscale/downscale that works; the punchy, mustard-spiked celery root salad counterpoints the eggs, which are topped with everybody’s favorite, but lesser-known herb, i.e., chervil. Add a handful of chopped chervil salad and you’ll thank me later. (I’ll also take a medal, if offered.) The dessert profiteroles at Grande Brasserie are similarly well-prepared. We liked them so much, we put them on the cover of my upcoming book, the revision of Ready for Dessert. And who doesn’t love a dessert where you get to pour your own chocolate sauce over? Is that the grin of a man facing a twenty-two-year wait to be cited for his love of French cuisine? I don’t have a photo, but Le Voltaire, a rather expensive restaurant in Paris, kept the œuf mayo valiantly on the menu for years, still priced at 90 centimes, about a dollar. Their other first courses range from €22.50 to €54 ($25 to $62), which may qualify it as the best bargain in Paris, but I don’t think you can just go in, order that, then leave. So the rest of the meal will make up for any shortfall. Before we went to Orléans recently… …I was looked up places to eat. We did go to a wine bar à manger (a wine bar with food), Les Becs à Vin, which had very nice natural wines, but it’s not a place to go to if you’re in a hurry. But I was smart enough to snag a table at Gric. Cheffe Marie Gricourt just took the honors for the best œuf mayo in the world for 2025, and it was kismet that I just happened to be heading to her city. Cheffe Gricourt and her team were super lovely, and it was nice that she and the two women cooking alongside her in the kitchen were the ones who brought the food to the tables, where they’d take a moment to tell you about them. Their award-winning œuf mayo comes out separated by tangles of celery remoulade, which I wouldn’t have minded a bit more creamy dressing mixed into it, sprinkled with crunchy roasted buckwheat groats. I’m still rooting for the home team, if I’m forced to determine which œuf mayo is “The best,” but the main courses at Gric were terrific. Romain loved his roasted lamb shoulder with green curry and bulgur wheat (below, left), and my gnocchis with ail des ours (wild garlic that was picked by the cheffe’s father), shavings of aged Comté, and the first local asparagus, was the best thing I’ve eaten in 2025.  When I told Cheffe Gricourt that, she told me the year wasn’t over yet. In my mind, let’s give that cheffe a medal for her modesty. How to Make Œuf Mayo at HomeYou don’t really need to go to a restaurant and order a $55 appetizer to have an inexpensive œuf mayo. And you don’t even need to come to France. Even if egg prices are higher than usual, it’s still a thrifty first course. You can serve each person just one egg per serving if you want to be frugal, although I do like how three egg halves look on a plate. If you want a precise recipe to make at œuf mayo home, with measurements and all that stuff, you can find a recipe in my book My Paris Kitchen. But like fixing yourself a sandwich, raise your hand if you’ve ever measured out the mustard or mayonnaise that you’ve spread on the bread? I didn’t think so. Making œuf mayo is simple. You want to start with hard-cooked eggs and have some runny, French-style mayonnaise on hand. American brands of mayonnaise can be a little gelatinous — Hellman’s+Best Foods, I’m looking at you…but you can give them a good stir to smooth them out, perhaps adding a touch of milk. You want it to be the texture of vanilla pudding. Since I discovered French store-bought mayonnaise, I rarely make my own mayo Nymore. The store where I get mine charges less than 3 bucks for a jar, and it’s made with free-range eggs and tastes delicious. Like most French store-bought mayo, there’s Dijon mustard in there to give it some savoir-faire. And for those concerned about eating raw eggs, the jarred stuff makes that point moot. To make hard-cooked eggs, start with room temperature eggs. Bring a medium saucepan of water to a boil, then reduce the heat a little to settle things down. Gently slide the eggs in, one-by-one using a spoon, so they don’t crack. Cook the eggs with the water at a steady, low boil for 8 minutes. If you like your eggs a little more cooked in the middle, let them go for 9 minutes. I avoid using the word “jammy,” however if you like your eggs runnier, you can cook them a minute less. Once cooked, drain the water from the saucepan, then jerk the saucepan back and forth with a little assertiveness until you hear some of the eggshells cracking. (But you don’t want to smash them.) Add ice to the saucepan, then fill with enough water to cover the eggs. Once the eggs are cool, peel them and cut them in half lengthwise. Put two or three halves on each plate and plop a good-size spoonful of mayo in the center. Want to put in on a bed of celery remoulade? Be my guest. A little greenery on there is nice. Chives are everywhere, so you can use those, but parsley or tarragon or chervil will do the trick. Don’t use sage, rosemary, or mint, which will lead the dish in a different direction. Although I mentioned that some chefs are taking the dish in different directions, keeping it simple is sometimes The Best. You're currently a free subscriber to David Lebovitz Newsletter. For the full experience, upgrade your subscription. |

Sunday, May 18, 2025

The Best Œuf Mayo in the World

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment