A Visit to Martin-Pouret Artisan Vinegar MakerThe master vinegar and mustard maker of Orléans, FranceA lot of people don’t think too much about vinegar. Olive oil gets a lot of press, but vinegar, it’s sharper (and usually less expensive) conjoint, gets short shrift. My first experience with good-quality red wine vinegar was when I was a teenager and at a friend’s house, and his mother made a green salad to go with dinner, and I’d never tasted a salad so good. It was simply a bowl of lettuce with dressing, but when I asked how she made it, she pulled out a bottle of Dessaux Fils red wine vinegar. From then on, I wanted all my salads to be made with that vinegar. Who knew that such an oft-neglected ingredient could elevate a salad and make it so special? Years later, when I moved to France, I tried to track down that vinegar, but to no avail. Perhaps it was one of those things, I thought, like French-cut green beans or orange French dressing, that exists in America but is unknown in France. I later learned Maille bought the company and shut it down in 1984, so no wonder I couldn’t find it. While many small and artisanal businesses have folded or been bought out, there’s been a strong “Made in France” movement in France, which, for some reason, they often say or write in English. But everybody seems to know what it means, and French people have always been staunch supporters of things made in France, although cheaper imports (or even products made cheaply in France) are everywhere. Nowadays, Made in France has become especially trendy—in a good way—and we’re seeing a big resurgence in high-quality foods and related products that are made in France, such as bakeries that make breads from heritage grains, small-batch apéritifs, tonic water (Archibald uses gentian rather than quinine, since gentian is grown in France whereas quinine has to be imported), as well as Paris-made cleaning products and kombucha. (Archipel fig leaf kombucha is my favorite.) So it was nice to see a rebrand of Martin-Pouret vinegar, the last vinegar maker in Orléans, who is still making vinegar the old-fashioned way and is the one I now buy. The company was started in 1797, and over the years, different generations of the family continued running the company, until, finally, no one in the family was interested in it anymore. So in 2019, two friends from college were looking for a “Made in France” project, and David Matheron and Pierre-Olivier Claudepierre bought the company, which fit the bill perfectly. The city of Orléans, in the Loire region of France, was once a major wine transportation hub for wine coming from the Loire and Burgundy on its way to Paris. Orléans also became known for its vinegar, and at one time, there were 200 to 300 vinegar makers in the city. Because wine is heavily controlled in France, back in the day, wine inspectors would sometimes find a wine didn’t conform to certain standards, or was turning, so it would be made into vinegar. The vinegar in Orléans was generally made from decent wine, though, rather than the worst. Edward Behr wrote in his excellent book, The Food & Wine of France, that wines from the Loire are affordable and light, positive qualities that Martin-Pouret still looks for when picking out which wines to make vinegar from. Many of the vinegars are sold by the variety of grapes, like wine, although there are also red, white, and even rosé vinegars. As we toured the production facility and aging cellars, they explained to me that everything here is as local as possible; even the cornichons and mustard grains are grown in the region. The mustard shortage last year didn’t affect the company since they get their mustard seeds from France, rather than Canada, where about 80% of other mustard makers in France get their seeds from.

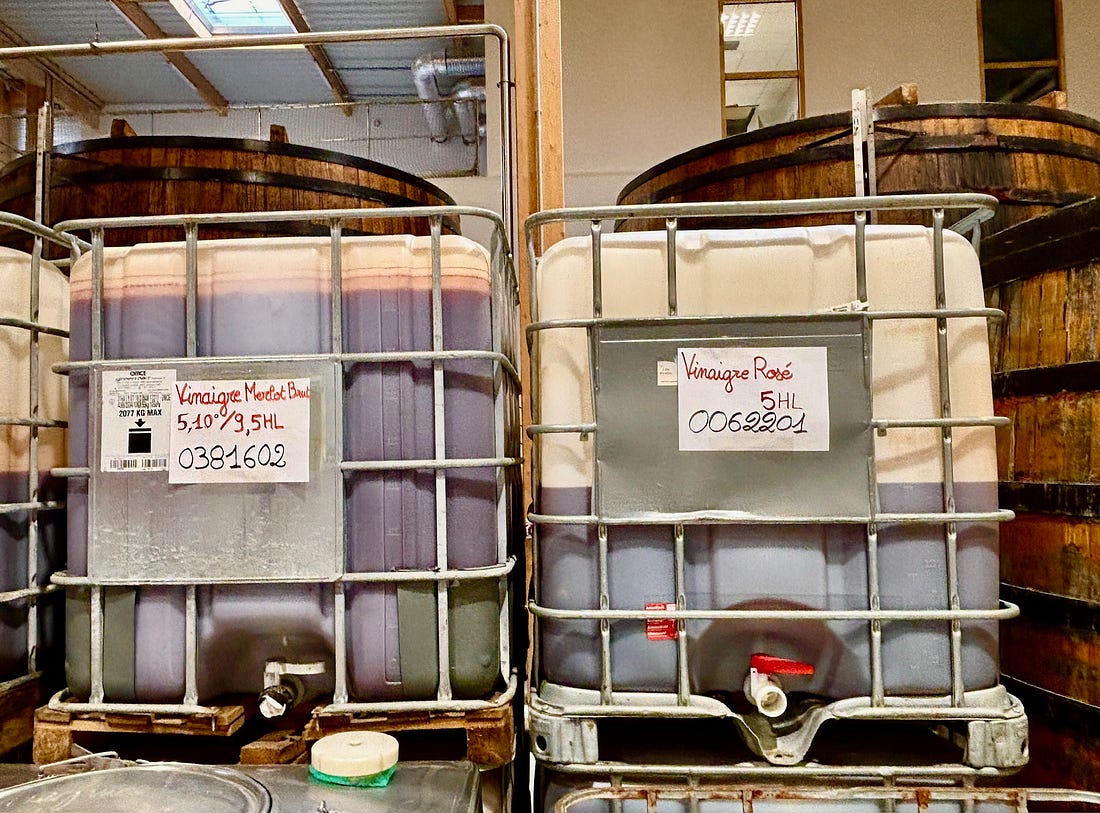

Same with cornichons. According to the French government, 80% of cornichons in France come from India, and most of the rest come from Eastern Europe. When I tried one of the cornichons at Martin-Pouret, which uses cornichons grown in the Loire region, the difference was remarkable. They were extra crunchy, not soft, as store-bought cornichons can be, and you could still taste the flavor of the actual cucumbers used to make them. They cost twice as much as supermarket cornichons, but now I’m hooked. The vinegar at Martin-Pouret is made by a method called the “Orléans process,” which is the slow method of making vinegar, aged in barrels. Most commercial vinegars are made from a fast process in steel tanks, rather than wood, that can take just a few hours. The Orléans process involves barrel-aging the vinegar in wooden vaisseaux, which are filled to only 60% of their capacity. The vinegar is treated like wine, an assemblage of sorts, where different wines and vinegars are mixed together by a master vinegar maker. Here, it’s Christophe Hemme. He’s responsible for every aspect of the vinegar process, from choosing and blending the wines to overseeing their aging and bottling. Vinegar here begins its life in small barrels, then gets moved to larger barrels, then goes back to smaller ones again to finish. The barrels he uses come from Bordeaux. When I asked why they didn’t use barrels from Loire winemakers, since we were in the region, he told me that in Bordeaux, because they want the wines to be tannic, they change the wine barrels every few years, moving them to new barrels made with fresher wood (which lends more tannins), so they sell off their older barrels. M. Hemme told me, when you start with mediocre wine, you get mediocre vinegar. When you start with good wine, you get good vinegar. Which makes sense. Above are the barrels in their final resting place. Each barrel will produce around 10 liters of vinegar, and you can see the fermentation happening on the surface of the vinegar inside when you peer into the holes in the barrels, which are intentionally kept open. I tried to get my cameraphone as close as possible to get a good picture, but you can sort of see the fermentation happening on the surface of the vinegar. And I have to say, the sharp odor in that room is so intense, it burns your eyes. After about 10 seconds, you want to leave. It’s really, really strong. When Williams Grimes of the NYT visited in 2000, he said of going into that room: “I was in agony. The vinegar attacked my lungs with a thousand needles.” After a few minutes, I got used to it. But it’s hard to hang around in there. The temperature in the room is kept at 27ºC (80ºF), which encourages the fermentation, and their total production is 400,000 liters of vinegar a year, which is around 700,000 bottles, all barrel-aged. They let us into a special aging cave with about eighteen (give or take) barrels with special cuvées for chefs they work with in France, coming up with special blendings that meet their tastes. But the most special is the one for the presidential palace in Paris… I didn’t ask for a taste, and I don’t suppose I’ll ever get one, since it’s quite precious, but if you go, they hold tastings of their range of mustards and vinegars in a sleek showroom at their production site, which opened in 2024. They also have a shop in downtown Orléans, which Romain and I visited three times in the two days we were there, to stock up and pick up gifts for friends. While they have a pretty substantial selection of white and red wine vinegars, made from Sauvignon, Syrah, and other grapes, there’s a trio of longer-aged vinegars that are aged 3, 6, and 9 years (above), and one that’s aged 10 years, which they poured for us to try. The presidential vinegar was quite lovely and smooth, and they even gifted me a small bottle to take home. I’ve amassed a whole lotta condiments in the last few years, so I may open a condiment museum in Paris to feature (and use) them all. But this vinegar will go to the front of the pack. Although, I still have a few bottles of very aged balsamic vinegar from a trip to Modena, Italy, in 2006, which are incredible, but are so good, they’re almost “too good to use,” as someone I used to work with used to say about things we were saving for a special occasion, but never used. So I hope this bottle doesn’t end up in the “too good to use” cabinet. With an eye on modern-day France, Martin-Pouret has expanded its condiment line from mustard to ketchup, which has become a very popular condiment in France. (So perhaps it’s something I can sell in my condiment museum’s gift shop.) In France, ketchup used to be considered très américain, but it actually originated in China, where it was developed over 500 years ago with a base of fermented fish. Other cultures and countries began making ketchups with ingredients like walnuts and mushrooms. The original tomato ketchup recipe was developed in 1812 by an American doctor and horticulturalist named James Mease, and it wasn’t sweetened. The ketchup at Martin-Pouret isn’t heavily sweetened, and I was especially intrigued by the smoked (fumé) ketchup, which the label reassured locals with more sensitive palates, was “subtilement fumé” (subtly smoked), but with the newfound popularity of hot sauces in France, whose consummation has gone up 30% in France in the last five years (sorry, but that can’t be attributed only to Americans here…), it was nice to find that the smokiness wasn’t all that subtle, so things are changing. Before we left, I got a look at where they bottle the mustards, while I decided which one(s) I wanted to bring home. They make thirty-two mustards, flavored with everything from cornichons to black pepper from the Île de Ré. Who knew they grew black pepper in France? There was also Honey & Chardonnay, Béarnaise with tarragon and shallots, sesame, and a mustard condiment that was made with figs, which also came home with me. The last thing I learned during my visit is that, in addition to being a cucumber that’s pickled in brine, cornichon also means ”idiot.” It was probably idiotic to haul so much mustard and vinegar home, since you can find it in Paris at shops like Le Pari Local, G. Detou, and others. One of the owners of Martin-Pouret did tell me it would be fun to start making their products in New Orleans, which might be a challenge since the world of transatlantic commerce is in flux. But perhaps if it’s Made in America—or Fabrique aux État-Unis— well, why not? Martin-Pouret You're currently a free subscriber to David Lebovitz Newsletter. For the full experience, upgrade your subscription. |

Sunday, May 11, 2025

A Visit to Martin-Pouret Artisan Vinegar Maker

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment